Somewhere between my third year of philosophical study and my growing pile of graded papers, philosophy stopped feeling like philosophizing. What had once been an exploration of life's deepest questions became mechanical box-ticking. I wasn't doing philosophy anymore, I was simply being quizzed on philosophical topics.

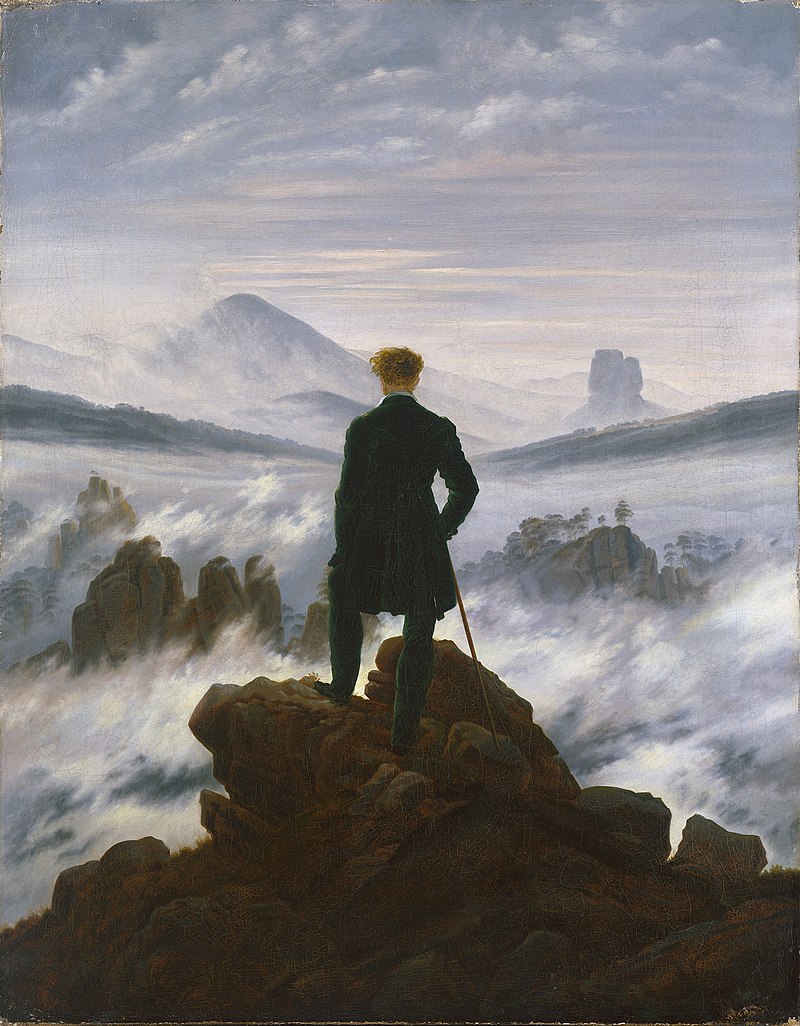

This realization gradually led me to the disenchanting conclusion that It was time to leave academia behind, not because I'd lost interest in philosophical questions, but because academic philosophy had lost touch with what those questions were supposed to illuminate. I was practicing a philosophy divorced from life itself. The focus on argumentative clarity had come at the cost of depicting reality as it is actually experienced. The rationalism was so abstract that I felt disconnected from the world, isolated from everything that had drawn me to philosophy in the first place.

This matters because I believe philosophy is fundamentally the art of building coherent understandings of life—of making sense in the broadest possible way—as a lived experience. Yet modern academic philosophy operates under a presupposition that Descartes embedded deep in our intellectual DNA with his cogito ergo sum. It assumes we must begin with some foundational certainty and build everything else from there. But there's nothing telling us that the world ought to be studied this way. Philosophy might also be done from the bottom up.

A Different Way of Understanding

Consider the stark contrast between Descartes and Heidegger. Descartes looked for an indubitable foundation from which to build everything with certainty. He wanted a bedrock of knowledge that could never be shaken. Heidegger, by contrast, looked at what is—within the immediate texture of life experience—and worked from there, trying to reach a coherent understanding at the most basic level of human existence.

I believe the second approach is the only one that human capacity can actually entertain, yet this isn't how I was being educated. I want to return to those ways of navigating understanding: observing first, then building theories, ultimately leading to a coherent "sense-making" of the entire life experience. Not abstract logical clarity that reduces everything to something it isn't just to achieve its methodological goals. Academic philosophy, as I experienced it, remained trapped in the Cartesian model, prioritizing logical clarity over experiential truth.

And by "observing" I don't mean empiricism in the scientific sense. I mean observing in the qualitative sense, I mean paying attention to the lived texture of experience before rushing to systematize it.

The Football Coach Analogy

Let me illustrate with an analogy. Imagine yourself as a football coach. Your priority is to train the team to win games, but crucially, the playing rules are predefined. Football doesn't allow touching the ball with your hands, intentionally hitting people in the face, or running outside the designated field area. As a coach, you take these rules as axiomatic starting points from which you then build your understanding of the best strategy for winning. A good coach goes further, considering each player's strengths and weaknesses, positioning them to minimize errors and maximize success.

This might sound different from philosophical inquiry, but it's not. The starting point—which may change at any time, just as football rules are updated regularly—is the de facto human condition we live in. The goal isn't "winning" in a universal sense (for in human life, "winning" varies by culture and perhaps even by individual), but rather achieving a comprehensive and holistic understanding of the playing field of human life itself. Achieving such an understanding finally enriches each person's ability to define and pursue their own contextual "winning".

A noteworthy clarification is in order here. When I speak of human life, as I just did in the paragraph above, I mean it in the sense that Kant famously articulated when he distanced the noumenal realm from our human grasp. We can only perceive phenomena as they appear to us humans. Nothing more, nothing else. It is therefore futile to try breaking through to the noumenal world by means of abstract rationalistic inquiry. It simply cannot be done. For all intents and purposes, only phenomena exist as worthy subjects of inquiry. Instead of constructing elaborate logical systems that claim to capture ultimate reality, we should focus on making sense of the world as it presents itself to us in our lived experience. This doesn't mean abandoning rigor or clarity, but it does mean recognizing that the most profound philosophical insights often emerge not from abstract argumentation but from careful attention to the concrete realities of human existence.

I'm leaving the academy not because I'm giving up on philosophy, but because I want to return to it. There are other ways to think deeply about existence, meaning, and human experience—ways that don't require sacrificing the richness of life for the clarity of argument. Sometimes the most rigorous thing we can do is resist the impulse to systematize too quickly, to let experience speak before we rush to translate it into academic prose.

The world is too strange, too complex, and too alive to be captured fully by any foundationalist project. It's time to start from where we actually are.

Comments (0)